|

Web story

Story #1

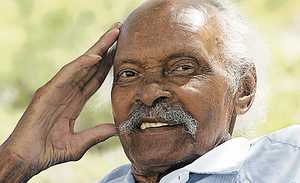

| Andrew Whitaker was a part of the Buffalo Soldiers |

|

| Living Legend |

WWII

Vet One of Last Buffalo Soldiers

Andrew

Whitaker was a part of the Buffalo Soldiers. Whitaker trained at Fort Riley, Kan. alongside future baseball legend, Jackie

Robinson.

TUCSON, Ariz. -- They were an anachronism -- soldiers on horseback in a war fought with tanks and

B-17s.

Nevertheless, here they were during World War II, patrolling the rugged hills and canyons along the border between

California and Mexico.

"They were about four-hour shifts. I would relieve you and your horse. We would ride back and

forth looking for men. We never found any," says Andrew Whitaker.

Whitaker, 87, was a member of the famed Buffalo Soldiers,

all-black units formed by Congress after the Civil War.

Nicknamed by the Indians they often battled against, the Buffalo

Soldiers of the U.S. Army became a fixture on the Western frontier, tasked with everything from escorting settlers and railroad

crews to fighting Indians.

Many of those Buffalo Soldiers were stationed at Fort Huachuca, which served as home for

several all-black cavalry and infantry units from the late 1800s until the Army was desegregated in 1947.

Not so for

Whitaker, however, who was drafted out of Chicago during the early months of the war.

His outfit, the 10th Cavalry,

trained at Fort Riley, Kan., headquarters for the Army's cavalry.

Also training there was future baseball great Jackie

Robinson.

"He slept in our barracks and went away to officer candidate school," says Whitaker.

It was at Fort

Riley where the Chicago city slicker encountered his first horse, up close and personal.

"You'd get up on the horse,

fall off," says Whitaker, who soon mastered the necessary horsemanship skills.

Harder to overcome were the prejudices

and hatred of some whites in 1942 America.

While rolling westward toward San Diego and their first assignment, Whitaker

and others were subjected to rock throwing and name calling by white soldiers during a stopover in Phoenix.

Apparently

the whites did not realize blacks were traveling on the same train - but in separate cars - until they got off at the train

station.

"We did not expect that," says Whitaker. "They were off on the siding. The train picked up speed and we got

away."

Final destination: Camp Lockett, built in 1941 near the small town of Campo, Calif., about 60 miles southeast

of San Diego.

For two years, cavalry troops patrolled the border and guarded water supplies and railroads.

"People

would ask, 'How can you still ride horses?' It was what was ordered," says Whitaker.

Practicality was also at play,

since much of the border was too rugged for vehicles to patrol.

Various horses were assigned to Whitaker during his

two-year stay at the camp, including one he called simply "Whit."

In 1944, the 10th Cavalry Regiment was inactivated

and its men transferred to other units.

With the cavalry's horses turned over to caretakers, the era of the horse soldier

in the U.S. Army had finally ended.

Some of the men were deployed to North Africa. Whitaker, however, received a medical

discharge for a shoulder injured while handling the horses.

He went back to Chicago, where in 1947 he saw Jackie Robinson

make his Wrigley Field debut as a member of the Dodgers.

In 1985 Whitaker moved to Tucson. Nine years later he would

be in attendance as Fort Huachuca officials unveiled a newly released stamp honoring the Buffalo Soldiers.

Though proud

of the Buffalo Soldiers and his time spent as one, Whitaker has no qualms about desegregation ending that proud institution.

"I

think it was a good thing," he says softly.

Story #2

Tuskegee Airmen to Be Honored in Washington Click here for story on the web

Tuskegee Airmen to Be Honored in Washington

Intrepid Fighters Will Receive Congressional Gold Medal

March 29, 2007 — In Washington today, 200 of the surviving Tuskegee airmen will receive America's highest civilian honor, the Congressional Gold Medal.

The airmen, who made up America's first all-black

combat flying unit, are recognized as some of the greatest heroes of World War II. Their skill and courage are the stuff of

legend.

The airmen formed as a band

of brothers who volunteered to fight for a segregated America that did not recognize them as equals at the time. Dr. Roscoe Brown, now in his 80s, remembers

the struggle.

"There wasn't a question [of]

could we succeed? It was the question, 'If and when will we be given the opportunity to succeed?' And once we got that opportunity,

we seized it," he said.

The airmen flew more than 200

missions escorting bombers. Although just recently disputed, the airmen are widely credited with never losing a bomber they

escorted to enemy fighters.

"They persevered and their

love of country dominated," said Sen. Carl Levin, D-Mich. "They're great patriots."

Combating Enemies and Segregation

The airmen were also determined

to change the face of the military. They became an integral part of its desegregation.

"We defeated segregation through

excellence of performance," Brown said. "We were given the opportunity in the highest profile activity to fly military airplanes

and we did it better than anybody else."

Col. Lawrence Roberts, father

of ABC's Robin Roberts, was a member of the elite team of fighters. He served in World War II, the Korean War and Vietnam. Today, he

will be honored in spirit along with his fellow airmen.

"I don't remember anything

like this receiving unanimous support from Republicans and Democrats in the House and Senate," Rep. Charles Rangel, D-N.Y.,

said. "What heroes, what a country that you can go from being treated like you're not a human being, and you come back a patriot,

that all America has to say thank you."

For Brown, the Congressional

Gold Medal is a much appreciated reward for a lifetime of service.

"The Congressional Gold Medal

is the epitome, like icing on the cake," he said. "It's just so wonderful to be recognized and for the country to understand

what we went through. You can't be prouder than that."

Story #3

|